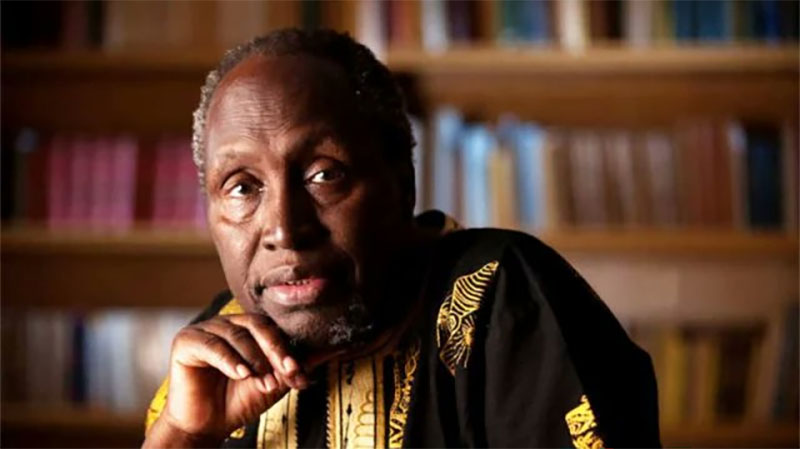

Photo Credit: Getty Images

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, one of Africa’s most revered literary voices, has died aged 87. A towering figure in postcolonial literature, his six-decade career chronicled Kenya’s journey from colonialism to independence and beyond—always with fearless honesty and unyielding moral clarity.

Born James Thiong’o Ngũgĩ in 1938 under British colonial rule, Ngũgĩ grew up in Limuru in a large, impoverished family. His early life was shaped by the trauma of the Mau Mau uprising. His brother, Gitogo, was shot dead by British forces—unable to comply with a command he could not hear due to deafness. Ngũgĩ’s village was razed, and his family, like thousands of others, was detained in colonial camps.

Despite these hardships, Ngũgĩ’s academic brilliance led him to Alliance High School and later to Makerere University in Uganda. It was there he shared his first manuscript with Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe. That debut, Weep Not, Child (1964), became the first major English-language novel by an East African writer.

By the early 1970s, with acclaimed works like The River Between and A Grain of Wheat, Ngũgĩ was hailed as one of Africa’s leading literary figures. But 1977 marked a turning point. He renounced his English name and colonial language, adopting the name Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and pledging to write only in Kikuyu.

That same year, his play Ngaahika Ndeenda—a critique of class inequality in post-independence Kenya—led to his arrest. Imprisoned without trial, Ngũgĩ wrote Devil on the Cross on toilet paper, defying state repression with unwavering resolve.

Exiled after threats to his life, Ngũgĩ spent over two decades abroad, holding professorships in the US and UK. His return to Kenya was met with public celebration—and brutal violence. An attack on him and the rape of his wife followed shortly after. He insisted it was politically motivated.

Ngũgĩ’s advocacy for African languages shaped generations. In Decolonising the Mind, he challenged the dominance of colonial languages in African literature, even calling out his former mentor, Achebe. His stance strained friendships but cemented his place as a radical literary force.

He is survived by nine children, four of whom are writers. His son Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ has publicly accused him of domestic abuse—a claim the elder Ngũgĩ never addressed.

From exile and prison to global acclaim, Ngũgĩ’s pen never wavered. He leaves behind a legacy unmatched, a voice that roared against oppression and dared Africa to speak in its own words.